(Bloomberg) — After three decades of stagnation in Japan, one of the most visible signs of renewal can be found in a stretch of old cabbage fields on its southernmost main island.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Apartment blocks, hotels and auto dealerships are springing up near a new semiconductor plant set amid farmland in the prefecture of Kumamoto, which has easy access across the seas to China, Taiwan and South Korea. The plant, operated by global chip giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., launched this year and one more is planned nearby. Wages and land prices in the area are up sharply, as demand feeds into a burgeoning ecosystem of suppliers and related businesses. With jobs opening up, the population is mushrooming.

Within an hour’s drive of the plant, however, the town of Misato shows more familiar scenes of economic distress. Once busy shopping streets are now lined with shuttered store fronts. The population is roughly one-third of its 24,300 peak in 1947. Instead, the number of roaming deer and wild boar is growing, prompting locals to protect their crops with netting.

Campaign posters for the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party line the main road as it threads its way through rice paddies. One of them declares: “Bringing you the feeling of economic revitalization.”

“I don’t feel it because we farmers are barely making ends meet,” said Kazuya Takenaga, 67, as he tended his fields of asparagus and rice. The rising costs of fertilizers, energy and utilities have eaten into Takenaga’s earnings. His two sons have left the town in search of work elsewhere.

The two conflicting images lay bare the biggest challenge for whomever the LDP chooses to becomes Japan’s next prime minister in a vote on Friday: Ensuring that a broad and lasting recovery takes hold across the entire nation — not just in certain areas.

The struggle to do that is one of the main reasons Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is stepping down, despite Japan’s economic gains. Nine candidates are vying to replace him as head of the LDP, which has led Japan for all but a few years since the 1950s and is almost certain to win a general election that must be held within the next year, not least because the nation’s opposition parties are weak and scattered.

During the campaign, the LDP leadership candidates have wrestled with the problem of rural decline and the unceasing flow of people from the countryside into cities like Tokyo. Some say the TSMC example provides a model that should be replicated around the country. Others emphasize tourism or incentives for businesses and academic institutions to shift into rural areas. All agree more needs to be done to boost birthrates, but few have new or radical ideas.

@AlastairGale and @ynohara1 explain https://t.co/bQZDETwgnj pic.twitter.com/lvs4zDSPqx

— Bloomberg (@business) September 25, 2024

Failure to broaden out the recovery risks leaving Japan firmly entrenched as a two-track economy, where the concentration of money and people is among the most extreme in the developed world. Businesses will increasingly struggle to find sufficient manpower and services, a phenomenon that is already evident even in Tokyo and other major cities.

To global investors, Japan is firmly back on the map. The stock market is close to record highs. Deflation appears to be vanquished. Money is pouring in for deals and investment, and the central bank is no longer experimenting with extreme stimulus. The Bank of Japan expects the economy to continue expanding more than its potential growth rate of as much as 1% a year.

Japan’s leaders are also becoming more confident on the world stage. While the US ally has long shied away from displays of hard power, it’s now rapidly beefing up military spending in response to concerns about China and North Korea, and becoming an influential voice on issues like support for Ukraine.

Since Japan’s defeat in World War II, a growth spurt through the late 1980s propelled it from occupied ruin to the world’s second-largest economy after the US. In 1992, when Japan’s consumer electronics were still the envy of the world, the country’s gross domestic product per capita topped the US at $32,000.

Yet some three decades later, it’s only ticked up to $33,000. Over the same period, International Monetary Fund figures show, per capita GDP in the US has more than tripled to $85,000.

Japan’s population started shrinking more than a decade ago and continues to decline by roughly 600,000 every year. Along with a lack of investment, that rapid depopulation has decimated towns and villages across the country. The door has opened slightly to foreigners of late, but permanent immigration largely remains a political taboo.

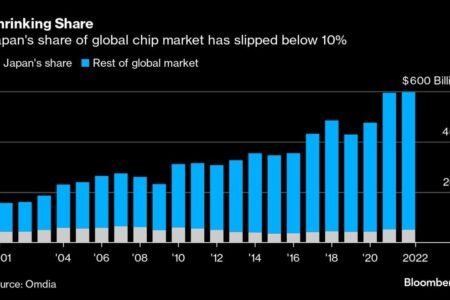

Demographics are just part of the challenge. Japan’s productivity ranks 30th among the 38 members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, a club of developed countries. Outside the auto industry, the stagnation has sliced through Japan’s manufacturing sector. As overseas rivals expanded their global share of chip production, Japan failed to keep pace. Through it all, entrenched deflation prompted authorities to make stable 2% price growth a key goal for re-energizing the nation.

That long economic stasis explains why there’s so much excitement now. Inflation is back as companies award the biggest wage hikes in decades, prompting the BOJ this year to raise interest rates for the first time since 2007. The government has also set aside about ¥4 trillion ($28 billion) to revive its chip industry, a strategy aimed at pushing TSMC and other companies such as Samsung Electronics Co. and Micron Technology Inc. to beef up operations.

“This is such a good place to be in right now,” said Chizuru Watanabe, who relocated from another part of the prefecture to take up an administrative role for Japan Material. “You can see great things are going to happen in the future.”

The city is also strategically important. The TSMC plant in Kumamoto has deepened Japan’s ties to Taiwan, a potential regional flashpoint if China ever moves to seize the democratically governed island. Those concerns have played a large role in Japan’s moves to boost defense spending to 2% of its GDP from 1% by 2028, and for the outgoing Kishida to repeatedly warn that Russia’s war in Ukraine might be a forerunner of a similar conflict in Asia.

Some of that cash is being spent on anti-ship missiles deployed at a base in Kumamoto that serves as the western regional headquarters for Japan’s army, known as the Ground Self Defense Force. Sitting roughly halfway between Tokyo and Taiwan’s capital, the base would likely play a major role if Japan is drawn into a regional war. A recent exhibition basketball game held in Kumamoto with a Taiwanese professional team shows how ties are deepening with an influx of technicians and plant managers from overseas, too.

For Takashi Kimura, Kumamoto’s governor, the buzz over the city’s economy can help with the problem of low birthrates and the flow of younger people to cities like Tokyo. If people are more enthused about the future, he said, they are more likely to have families and stay put. Moreover, he added, the growth of the semiconductor supply chain in Kumamoto will eventually reach the more economically vulnerable parts of the prefecture. One local financial group estimated the chip-making project will generate about $80 billion in economic activity through 2031.

“For 30 years our national economy has been closed off,” Kimura said in an interview. “But Kumamoto’s opening up to Asia shows the way forward for Japan’s economic revival.”

Yet in Nagomi, another town a short drive from the TSMC plant, pessimism runs deep. About 40% of the town’s 9,000-or-so residents are 65 or older. Last year, 188 residents died and only 44 babies were born.

Mayor Yoshiyuki Ishihara said he doesn’t expect much will change when Japan gets a new leader. “Few policies have left an impression on me, and not many of these measures have really reached the countryside directly,” he said. “I hope they will develop policies that do make the regions more prosperous.”

Few Japanese residents of small towns like Misato and Nagomi have money invested in markets, private pensions or any kind of stake in M&A activity. The return of inflation is a shock for people who haven’t experienced rising prices in three decades. Imported essentials like food and fuel are suddenly more expensive, compounded by the yen’s weakness.

On the campaign trail, candidates for the LDP leadership election are speaking more to cost-of-living concerns than trumpeting the positives of rising prices. Sanae Takaichi, who has been climbing in the polls, has called for more income support for the most vulnerable in society. Another top candidate, Shinjiro Koizumi, bemoaned the disappearance of national economic champions.

“To put it bluntly, Japan is in decline,” Koizumi said during an LDP leadership debate in Tokyo earlier this month.

“The high growth of the postwar years was led by companies such as Honda and Sony,” he said. “They started from the town level and they conquered the world. However, in the past 30 years, no such company has emerged.”

Still, the Japanese public’s overarching desire for stability limits the scope for drastic policy changes, just as it allows the LDP to maintain its grip on power. Opposition parties have consistently struggled to offer voters a compelling alternative, and any attractive policy ideas they come up with are often quickly co-opted by the LDP.

Until now, Japanese politicians on all sides haven’t produced any immediate solutions for persistent structural problems like population decline, according to Hideo Kumano, a former BOJ official who is now an economist at Dai-Ichi Life Research Institute. The TSMC plant in Kumamoto is good for the local economy, he said, but there is a limit to the impact.

“You’d need a similar economic effect around the country to really revive the national economy,” Kumano said. “And that is one very big challenge.”

That’s an existential problem for places like Misato, which is among 744 municipalities in Japan facing the risk of extinction as their populations decline. Kousei Motoyama, 71, chairman of the town’s chamber of commerce and a long-time LDP supporter, said he wants the next prime minister to ensure that small towns like Misato don’t get left behind. He was hopeful the benefits from the TSMC plant would reach the town, but also wanted more government support for agriculture.

“You can’t keep living here if they don’t make the economy better,” said Motoyama, who owns a small construction firm. “Our way of thinking about business may be old-fashioned, but we are the people who have supported Japan for a long time.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Read More: Japan’s Economic Revival Is Failing to Save Its Vanishing Towns